@mdvfunes Isn’t it great like that, that we can learn so much from what others look at and write about?!

— Christina Hendricks (@clhendricksbc)

Yes, it is!

So this weekend I had intended to work on the radio show, perfect my audio voice and re-do my work over and over to get it ‘perfect’ whatever that means. Instead I went on another design safari with Ds-ina. She wrote a blog post that ended with:

It took me over a week to finish this blog post, and probably it’s far too long for anyone to read through the whole thing.

Well, Ds-ina you were wrong; not only did I get to the end but read it more than once and followed up your links as you had explored different stuff from me though we both started from the same document. I liked the fact that your post was sharing personal learning, reflecting on personal struggle and not trying to establish the rights and wrongs of design. I too struggled with many new concepts and challenges to deeply held views on design week. It is something I want to keep learning about – may be next time I do DS106? Did I just write that? I decided to strike while the iron was hot and just go on a new design safari with Ds-ina. What follows are my reflections from her post and new thoughts it led me to explore.

I started with this comment as the post explored colour and its use in design:

Is this a good use of colour? Honestly, I have no idea. Are the colours used complementary in some way? Should they be? Why are these particular colours used, and why are some colours on top of others—what guided that choice? No clue. All I can go by is what seems pleasing to me, and I do like this one. I think the contrast of the colour and the dark-ish glass is nice, and the colours are spaced in a way that seems balanced.

This spoke to me at many levels. It suggested to me it is one thing to notice design elements and another to feel able to say if something is good design. This resonates strongly with my own explorations. Ultimately I too went back to a visceral like/don’t like criterion which is what Donald Norman suggests design is about. He says a small percentage of what we choose as good design is reflective in nature (i.e. we choose consciously in line with our values) but the majority is visceral, behavioural and unconscious. Good design makes us happy. So, as we see something pleasing, a surge of dopamine hits the brain and generates positive emotion. We cannot explain it with language, but we feel it.

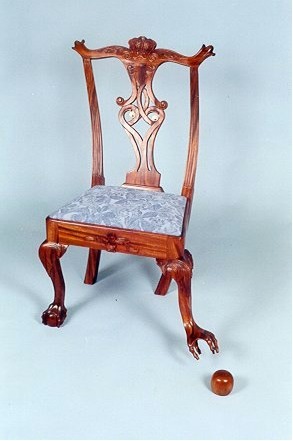

Norman illustrates this in many ways ( the short video is a design safari itself – and great fun to watch) but my favourite example is this:

This is Jake Cress’s chair with flaw.

It comes with a short story. This poor little chair knows it is flawed and it is working hard at trying to fix itself. Norman says that what is interesting about this is that we believe the story and are emotionally affected by the object. We like it. I have linked to Jake Cress’s website (click on the photo) – worth a visit if quirky furniture that tells story is your thing.

This connected for me with the video by Paul Zak during the initial weeks of DS106. There we learnt that increased production of cortisol and oxytocin are found when stories are told that fit Fraytag’s dramatic arc – exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and denouement – and that this makes us behave in ways we may not have chosen to behave before we heard the story. Zak proposes that stories are changing our brain chemistry. In the same way that Norman says our brain chemistry is changed by good design.

It is a difficult job then for any budding designer to determine how to make people happy so that they like their designs. As I continued to read Ds-ina’s post I began to see a pattern. Designers are trying to create conscious heuristics or principles that may lead to people’s happiness ( or their emotions being affected in some way)

Ds-ina in her post explores symmetry for example. She quotes this article,

Symmetrical balance occurs when the weight of a composition is evenly distributed around a central vertical or horizontal axis. Under normal circumstances it assumes identical forms on both sides of the axis. When symmetry occurs with similar, but not identical, forms it is called approximate symmetry.

I had been struggling with the idea of approximate symmetry, but she shows us a photo that explains it beautifully.

People, but not of the same sex or doing the same action! I now get approximate symmetry. What this has done is given a heuristic to understand why I may have a positive emotional reaction – I like it – to this sign. There are many signs that have useful purposes, such as helping us to recycle more, and design principles may or may not be applied to these. Ds-ina’s post goes on to explore some objects and signs as she continues her design safari around her university campus. I encourage you to read her post for a clear and well supported explanation of many principles we covered in design week. I particularly liked her examples about minimalist principles and asymmetrical balance, which for me until I read her post, had been a contradiction in terms.

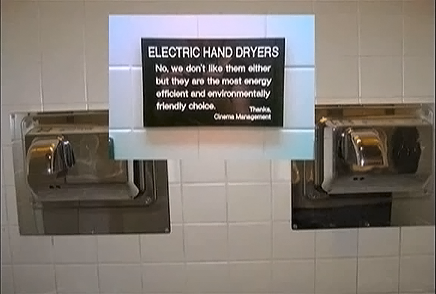

As I went further on safari with Ds-ina, it put me in mind of the idea of emotionally intelligent signs. The notion that we are more likely to take action on a sign that appeals to our emotions and particularly signs that are empathetic to our experience such as this one,

This sign singlehandedly changed my view of electric hand dryers a few years ago.

I then spend several hours watching Objectified again and again. I have mentioned this film in a previous post. It really challenged my views about what makes good design. It goes beyond notions of aesthetics and brain chemistry and makes us stop to think about the intent of design. it suggests that we need to think systemically not individually about design; that non-disposability, and longevity matter; that there is a reality to be faced about how objects that have been thoughtfully designed are just landfill fodder for the future. Many examples and images later, that tell a story of waste and consumption, I am ready to sit up and listen to the suggestion that what Norman calls the reflective level of good design may need much more attention that we give it. Both in object design and in designing our personal cyberinfrastructure.

I kept going back to Ds-ina’s post and noticing the discomfort she expresses with evaluative criteria that are from the purely personal realm. The whole safari seems a quest for more impersonal criteria against which design could be judged. I found myself in the same place during design week. I was happy to come back to ‘art in the brain’ as a foundational principle, but something kept nagging at me too. So I explored further the ideas in the film as I felt that an answer might lie beyond the personal and my love for creating ephemeral artefacts.

I found the seed of an answer in Tim Brown from IDEO talking about design thinking.

I can only say ‘watch it, now!’ But here is his view of what design has become. From,

systems thinkers who were reinventing the world, to a priesthood of folks in black turtlenecks and designer glasses working on small things. As our industrial society matured, so design became a profession and it focused on an ever smaller canvas until it came to stand for aesthetics, image and fashion.

In the world of digital storytelling I guess this equates to using our shiny digital toys to make stuff look good without a thought for the crafting of the story and its place in the wider world. I think that these ideas challenge us to think beyond individual creativity and look systemically to the intent of the storyteller and the actions our stories encourage.

His answer? Moving away from design and towards design thinking. He calls for ‘a shift to local, collaborative, participatory design thinking. ’ It suggests a set of design principles grounded not in psychology, not in individual aesthetics, but in community and what David Kelley calls a common ethos of empathy for the consumer. it uses rapid prototyping as a tool that puts potential ideas into the hands of users and gets users to assess value. Kelley says ‘it is not rocket science, it is just empathetic to people’. This is the approach that gave us Apple’s original designs, they worked with Steve Jobs in the early days. This to me has hope. It is defined as ‘human-centered design’. It encourages creative confidence as the ability to ‘to fail often, to succeed sooner’ and as the ability to come up with ideas and having the courage to try them out. This implies to me that what we try does not always succeed, that we should assess this according to an external criteria of how others engage with our designs, and that we need the courage to remove and delete what does not work, and try again. In turn, this requires that we look in the mirror and question our givens – and just why do we like that? The design thinking approach further encourages us to ask: Should we like that? What is the larger purpose that my individual creativity is serving? For some the answer is in social change as in the example of Southwark Circles as a new way to care for the old, for others about open education and using it to teach this approach to design. Yet others want to focus on younger people and how to support them in this kind of thinking.

If we change brain chemistry and the way people act by the stories we tell, then may be we have a responsibility to press pause and question our intent as storytellers. The wider purposes, our responsibilities as storytellers to ourselves, our communities and the wider systems we belong cannot be ignored when looking at the issue of design principles in digital storytelling. Jonathan Worth may be on to something when he says we have to teach the ‘gravity of the role of the storyteller’. Perhaps there is space to add a week on this topic in future runs of DS106?

I have learnt much and much remains to be learnt.

I take away the need to hold the tension of opposing views as the frontier where new ideas are born and how tough it is to do that without the mind grasping for simple solutions. Thanks, Christina for taking me on such an insightful safari and encouraging me do a second one of my own that has led to deeper insights.

Leave a Reply